A mega Mugler moment

Simply sign up to the Fashion myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

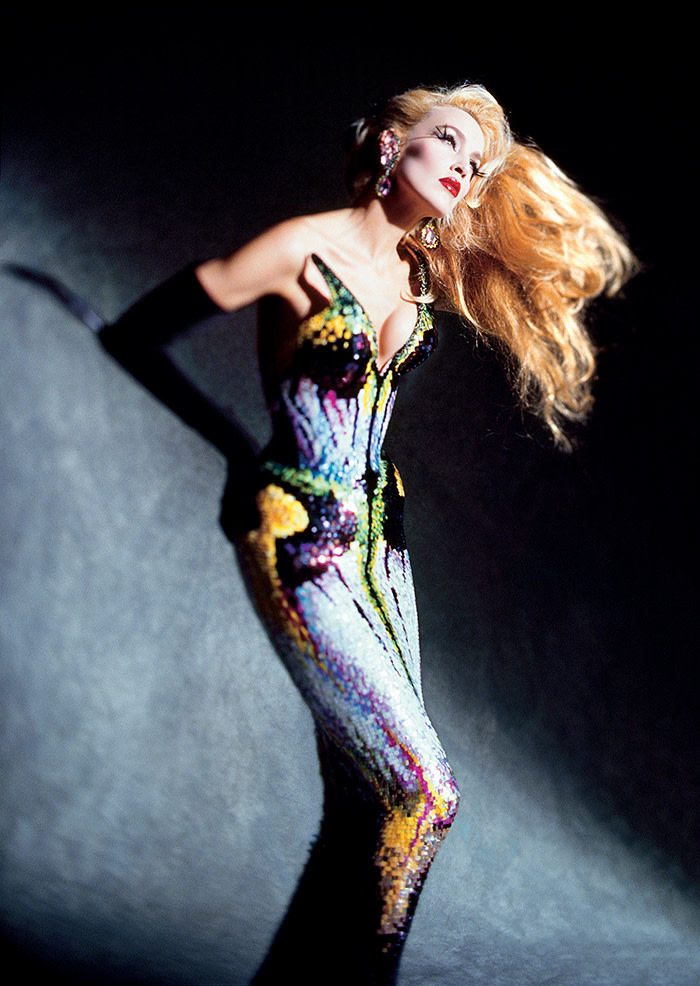

At last month’s Grammy Awards, rapper Belcalis Marlenis Almánzar — better known as Cardi B — wore an old dress. Some 24 years old, in fact, from Thierry Mugler’s autumn/winter 1995 collection: an haute couture ode to Botticelli’s Venus that saw Ms B’s pearlescent torso emerging from a spumey conch of baby-pink duchesse satin. Many observers didn’t know the past of the dress, first worn by model Simonetta Gianfelici. They just knew that Cardi had stolen all the attention — and continued to do so, by wearing two further Mugler outfits during the ceremony, all pulled directly from the Mugler house archives by her stylist Kollin Carter. A week or so later, Kim Kardashian popped eyes at the obscure Hollywood Beauty Awards in another Mugler dress, originating from 1998 and resembling a back-to-front vest-top with a strip of duct-tape over each otherwise exposed breast.

Does it say something about the state of fashion that against a background of the neutered, desexed and homogenised cookie-cutter clothes that populate premieres and awards ceremonies, these high-profile, high-impact women are turning to clothes over 20 years old to make an impression? Or maybe it’s simply a testament to the colossal talent of Mugler that his clothes can still provoke more heated reaction than their contemporary counterparts.

This year, Mugler’s work is recognised in two exhibitions. The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute spring exhibition Camp: Notes on Fashionwill feature multiple Muglers among about 200 items by designers including Vivienne Westwood, Marc Jacobs and Gucci, the show’s key sponsor. Meanwhile Thierry Mugler: Couturissime is the first retrospective devoted entirely to the now 70-year-old designer, who was born in Strasbourg and trained as a ballet dancer before fashion beckoned.

“An impossible project,” was the summary of show curator Thierry-Maxime Loriot, who devised the exhibition alongside Mugler. Consisting of about 150 outfits, with 100 photographs from Helmut Newton, Richard Avedon, Guy Bourdin and Mugler himself, it is at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) until September 8 — a slightly odd location for a show on a designer who was the toast of Paris and a favourite of Hollywood. Indeed, institutions including the Met, the Palais Galliera in Paris and London’s V&A have approached Mugler about staging a retrospective.

The impossibility wasn’t the subject-matter, but the designer. Mugler is, by repute, a control freak. He began taking pictures when he got so pernickety on-set with Newton that the legendary German micromanager thrust the camera into Mugler’s hands and told him to do it himself. His clothes often required months of work to perfect, refashioning the body inside them via corsetry and padding, moulded leather and latex. Since leaving the fashion house that still bears his name in 2003, Mugler’s mania for control has expanded from refashioning women’s bodies to his own — he has renamed himself Manfred and pumped up his own physique, via gym regimens and apparent plastic surgery.

“Mugler has been very vocal about what he wants and what he doesn’t want,” says Loriot. “He doesn’t do interviews — and didn’t do interviews . . . He wouldn’t lend to a magazine if he didn’t like them.” The same is true of museums — although the house of Mugler (owned by Clarins since 1997) controls an archive of fashion pieces and loaned the majority in the show. Clothes also came from celebrities, and the museum had access to Mugler’s own archives.

The catalogue for the exhibition is glossy, the line-up of exhibits impressive. It has taken three years of work. “He wanted to have my vision of his work — that it would be a celebration, not like a funeral,” says Loriot who, with the MMFA, collaborated with Mugler to bring his creations back to life. It includes costumes created by Mugler for the Comédie Française’s 1985 production of Macbeth, and the first collaboration by the Helmut Newton Foundation on a non-monograph exhibition. There is also input from the visual effects company Rodeo FX, which has created artworks for Game of Thrones and Blade Runner 2049. Here, they create a virtual environment of Mugler’s trademark fantasy animals and insects.

A 42-year-old Québécois, Loriot was the curator behind the globe-trotting show The Fashion World of Jean Paul Gaultier, which spent five years touring museums and was seen by more than 2m people. That exhibition had a catwalk of oscillating outfits and animated mannequin faces that chattered as you roamed through Gaultier’s greatest hits. A Mugler show is, perhaps, the natural next step from Gaultier. “You could call it Gaultier on steroids,” says Loriot. “These exhibitions are not for people of the fashion industry. You have to make something very special to attract.”

Fashion does attract — especially flashy fashion, like Mugler’s. The Met’s 2018 Costume Institute show Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination, had more than 1.6m visitors, the most-visited exhibition in the institution’s 149-year history; Christian Dior: Couturier du Rêve broke records for Paris’s Musée des Arts Décoratifs with over 700,000 visitors; and the Alexander McQueen retrospective Savage Beauty was the most successful ever at the V&A — a return on an exhibition cost of £3m. MMFA is hoping for the same reaction to Mugler, which is already due to tour to Rotterdam and Munich. “It’s easier to see a Picasso than to see a Mugler,” says Loriot, hawking the show.

Arguably, nothing is selling Mugler better than archive Mugler on real women. That’s quite exceptional — museums require you to wear gloves while handling archival fashion, lest the acid on skin damages their longevity. And Mugler’s fetishistic, fantastical vision of woman is utterly at odds with the desexed cultural mood of the moment — as it was often in his heyday. “His vision of a woman could be seen as reductive,” says Loriot, “but he was inspired by powerful women, superwomen. He lived in a world of women.”

Loriot cites a conversation between Mugler and feminist writer Linda Nochlin in New York Times Magazine in 1994 as proof of an odd shared ground on female empowerment. I would say the women in these clothes are further evidence. And this exhibition is worth a viewing, because designers aren’t creating clothes like this any more — hence, you’ll never see anything quite like it again. Until the next celebrity goes digging in the archive, that is, and wears their own bit of fashion history.

Follow @FTStyle on Twitter and @financialtimesfashion on Instagram to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments