Europe car groups face huge profit hit to cut CO2

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Forget the global trade war, declining sales or even Brexit — the sternest challenge facing Europe’s car industry comes from the exhaust pipes of its vehicles.

Strict new carbon dioxide emissions targets will be phased in next year across the EU, with the threat of punitive fines for those who fail to comply.

Yet the industry, broadly, is not ready.

“It’s going to be a hell of a job,” Carlos Tavares, the chief executive of Peugeot owner PSA, said last month. “But we are going to meet them, whatever it takes.”

Under the rules, carmakers must cut their average fleet emissions to less than 95 grammes of CO2 per kilometre by 2021.

They face a €95 fine for every gramme of CO2 that exceeds the target — multiplied by the number of cars sold that year.

“We are talking about a potential €30bn penalty for the industry,” Volkswagen chief executive Herbert Diess warned investors at the company’s annual capital markets day.

Yet emissions are heading the wrong way.

CO2 emissions from new cars are rising as consumers shun diesel models and opt for petrol alternatives, while the shift towards heavier sport utility vehicles increases pollution levels further.

New data for 2018 showed average emissions rose to a four-year high of 121g of CO2/km, according to Jato Dynamics, an auto data supplier.

Sales of SUVs, which are heavier and therefore produce more CO2 than traditional saloons, have risen by three quarters since 2015, according to IHS Markit.

Another complicating factor is the sharp decline in diesel sales.

Buyers lost faith in the eco-credentials of diesel cars following the Volkswagen scandal of 2015, when it emerged that the cars produced far higher levels of harmful nitrogen oxides than advertised.

The scandal dealt a blow to diesel — and to carmakers that had been relying on the fuel to cut CO2 emissions, as diesel vehicles typically emit a fifth less carbon than petrol cars.

Diesel vehicles accounted for as much as 56 per cent of EU sales in 2011, but last year the share fell to 37 per cent.

All this has left the industry in a bind.

Arndt Ellinghorst, lead auto analyst at Evercore ISI, described the CO2 challenge as the “biggest structural headwind” facing the sector — even more potentially damaging than trade wars with China, US tariffs, diesel bans and Brexit.

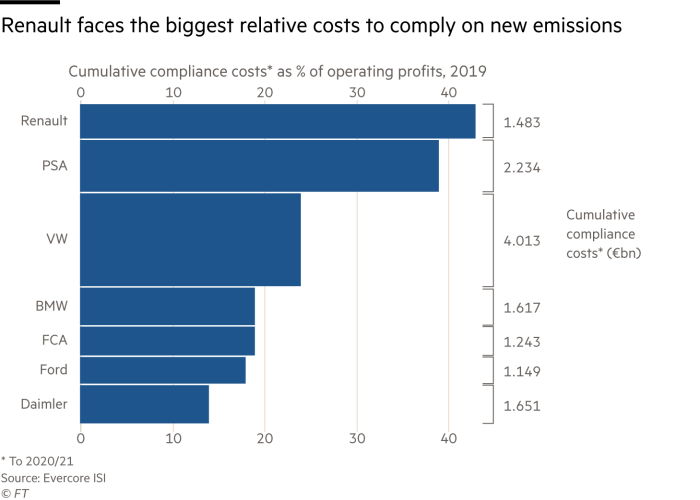

He estimated it will cost the industry €15.5bn just to make its vehicles compliant.

The 95g/km target becomes valid next year for 95 per cent of a car brand’s sales. The phase-in period is meant to give carmakers some leeway as they come to grips with the new rules.

Many manufacturers are relying on “supercredits” from electric cars that offset more polluting vehicles, which partly explains the deluge of battery models arriving on the market in the coming 18 months, even though sales of electric cars account for less than 1 per cent of the market.

But battery costs mean many of these cars have thinner margins than traditional vehicles. Some are even lossmaking.

“Either you increase the price of your vehicles, and clean mobility becomes elitist, and possibly you do not meet the numbers you need to avoid penalties . . . or you sell at a loss, and you need to restructure your company to compensate,” Mr Tavares said, laying out the challenges facing auto executives.

The timing could not be worse for carmakers, which will be forced to sell these lossmaking models to comply with the rules coming just as the industry cycle begins to decline.

“It’s a toxic cocktail for the carmakers,” Patrick Hummel at UBS said. “The sales cycle has peaked, CO2 compliance is a headwind and they have ever-increasing spending on technology.”

The bank estimated that total European car earnings for 2021 will be €7.4bn lower because of the cost to meet targets. This is a cut of about 14 per cent versus 2018.

For some carmakers, the hit to profits could be considerable. To comply, PSA, which is the furthest behind, faces a 25 per cent reduction to earnings per share in 2021, it forecasted.

Profits at others will face a hit, with UBS forecasting a 13 per cent drop at VW, 10 per cent at Renault, 9 per cent at Daimler and 7 per cent at BMW.

VW, which sold 4.4m vehicles in Europe last year, has average emissions of 123g/km, “a huge gap, which is very hard to close,” Mr Diess said, even though it is closer than many of its peers.

Yet not all of the carmakers are in a state of crisis over the targets.

Toyota, which embraced hybrid power more than a decade ago, expects that half of all cars sold in Europe this year will contain the technology.

It has raised a previous 2021 target for hybrid sales from 50 per cent to 60 per cent.

“The development of hybrid has been even faster than we anticipated,” Toyota’s European chairman Didier Leroy told the FT at the Geneva Motor Show last month.

Toyota also became one of the first companies to kill off diesel from its mix, raising its CO2 output initially but helping it decouple from the free-falling diesel market, while the company will also launch three new battery-only cars in Europe by 2021.

Others are shifting the mix of cars they sell in efforts to comply.

Renault chief executive Thierry Bolloré said the company wants to make every vehicle a “contributor rather than an offender” in lowering the French group’s emissions, something that could see the company discontinue the most-polluting engines from its existing line-up of cars.

Fiat Chrysler chief executive Mike Manley previously told the Financial Times the company may pull its most-polluting models from showrooms.

The company has also taken drastic action to avoid penalties, forming an “open pool” with Tesla, agreeing to pay the electric pioneer hundreds of millions of euros for its zero-emissions cars to be counted in its fleet, as reported in the Financial Times.

This is an extension of the scheme that allows brands under the same owner, such as Lamborghini under VW, to pool their emissions together to avoid fines.

FCA’s move suggests carmakers have little choice but to comply.

Penalties for missing the target are not only steep, but the reputational damage could translate into lost sales as more businesses adopt their own CO2 targets, as businesses that lease vehicles may switch to an alternative supplier.

Paying fines rather than investing in technology is also a poor strategy given that after 2021, it gets tougher. By 2030, the EU is targeting car emissions to fall another 37.5 per cent.

But Julia Poliscanova, senior director at Transport & Environment, a green-energy lobby group, said allowing rival carmakers to combine their emissions was a “’get out of jail’ card”.

She accused the industry of “just crying wolf that they cannot meet the target” and selling more SUVs now in order to make the targets look especially onerous.

“There are so many pathways to meet the target,” she said. “We really don’t think they will have a problem complying.”

Unintended consequence: death of the small car

One unintended consequence of the EU’s 2030 emissions targets could be the death of the small car.

Max Warburton, analyst at Bernstein, said the cost to equip small, low-margin cars with batteries and electric engines to meet ambitious EU CO2 targets “looks totally unaffordable”.

Even the cheapest “mild hybrid” system would cost between €600 and €1,000 per car, he said. A full hybrid system would cost between €2,500 and €4,000 per car.

Volkswagen chief executive Herbert Diess has acknowledged that cheap small cars such as the Up! and the Polo will “never” meet the 2030 targets. “Those models are really under threat,” he said.

Felipe Munoz, an analyst at data provider Jato Dynamics, warned Chinese groups will step in to provide Europeans with small cars if the region’s producers struggle to manufacture them at affordable prices.

“With these very tough targets, the only winner here is China,” he said. “They are already working on small electric cars and they have an advantage in volume.”

Patrick McGee

Comments