How 3D printing will transform mass production

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

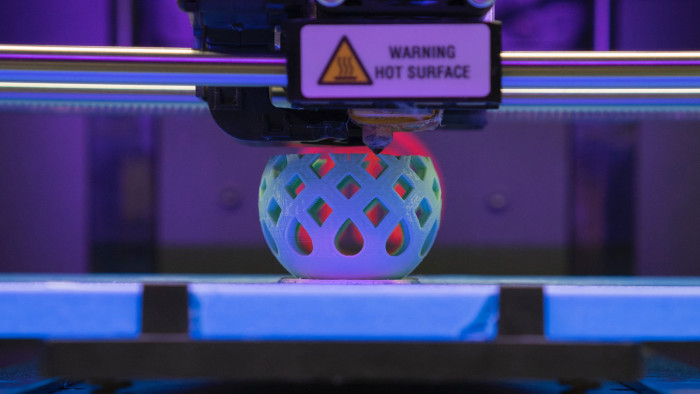

Star Trek featured a glowing device called a “replicator” that can create any object out of thin air. Now, advances in 3D printing are bringing science fiction a step closer to reality.

While the technology cannot yet produce anything you want on the spot, the materials that can now be printed include metals, glass, ceramics, carbon fibre and various plastics and resins.

More dramatic changes lie ahead. Several experts speculate that future consumers may enjoy easy access to high-quality 3D printing facilities that can produce a range of products from a custom-shaped bicycle seat to a replacement handle for a refrigerator.

The situation may be similar to 2D printing today, says Robin Kleer, an associate professor of innovation management at Vlerick Business School in Belgium. Printing a few pages at home is easy and affordable, but more complex products, like posters or pamphlets, require specialised shops.

“I can imagine local shops arising that you can walk to print things out,” says Mr Kleer.

This reality is already taking shape. In the US, UPS offers 3D printing in about 30 stores, but the items it produces are basic.

The spread of 3D printing will challenge the traditional model of mass manufacturing. A study on the likely effect of the technology in the coming decades, co-authored by Mr Kleer, noted that in future having established manufacturing and supply chains will no longer give providers the edge. Instead, they will need to be more agile with ready access to customers and designers.

Nadav Goshen, chief executive of MakerBot, which makes 3D printers, says the technology will “lower the barriers to entry for manufacturing”. The company is now marketing its latest devices to small and medium-sized enterprises.

Some mass manufacturers are embracing the opportunities that 3D printing offers to become more responsive to customer demands.

Ikea, for example, has unveiled prototypes of bespoke ergonomic attachments for desks, mice and keyboards that it developed with partners including UNYQ, a company that prints 3D prosthetics.

The line is set to launch in 2020, with computer gamers the main target. Customers will submit their measurements via an app and receive the accessories by post.

The attraction of 3D printing goes beyond customisation. It also allows large companies to launch products more quickly, says UNYQ chief executive Eythor Bender.

“In an ideal world, you could look at an Instagram post and turn that into a design that can go out the next day,” says Dávid Lakatos, chief product officer of Formlabs, which has printed personalised razor handles for Gillette.

The move from mass production also allows manufacturers to make their operations more local. “A lot of companies are looking for ways to shorten supply chains and to bring their factories closer to their customers,” Mr Lakatos adds.

This reduces the need to ship mass-produced products from jurisdictions with lower labour costs, which increases supply-chain security and reduces carbon emissions.

3D printing could also help manufacturers protect the planet’s finite resources. Traditional manufacturing often means whittling down a block of raw material or estimating how many units to run off a production line — some of which are never used. 3D printers can turn out exactly the right number of products with less waste.

The environmental picture is not clear cut, however. While setting up a line for mass production involves huge costs in investment and energy, once the plant is running each object is efficient to produce. A 2012 study of one 3D printing method found that it was more energy efficient at making 300 parts or fewer. For larger volumes, the economies of scale of a production line won out, although this study did not consider transport emissions.

As with any new technology, there will be drawbacks. Barry Berman, a professor at Hofstra University in the US, raises the question of protecting intellectual property. “Is someone going to take my computer design and knock off my product?” he asks.

He also says that a shift from traditional factories to more, smaller production sites could compromise quality control. The standard way to test a product today is to pick a sample off the line and subject it to extreme conditions. This method is not possible with one-off products. Instead, companies have to test the printing process for quality.

Despite these challenges, 3D printing is expected to be transformative. Irene Petrick, senior director of industrial innovation at Intel, says that manufacturers’ ability to produce one-offs or small batches of custom items more easily will upend current mass production — a shift not seen since the industrial revolution.

Comments