China censorship drive splits leading academic publishers

Simply sign up to the Chinese politics & policy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The world’s leading academic publishers are deeply divided over how to respond to China’s intensifying censorship drive at home and abroad, with some vowing to resist while others have caved in to pressure.

Western university presses and their commercial rivals have locked swords with hostile censors for hundreds of years but academics say the scale of the challenge they face from China today is unprecedented.

Having silenced many of his domestic critics, President Xi Jinping is seeking to export the Chinese Communist party’s heavily circumscribed view of intellectual debate as part of his push to promote Chinese soft power.

Jonathan Sullivan, head of the China Policy Institute at the Nottingham University, said western institutions are unprepared to deal with Beijing’s efforts to change the west and are too prone to surrender their principles for the promise of market access.

“China can do what it likes at home but the real issue is for western academia, media organisations and other companies,” he said. “As is China’s wont, they are dividing and ruling.”

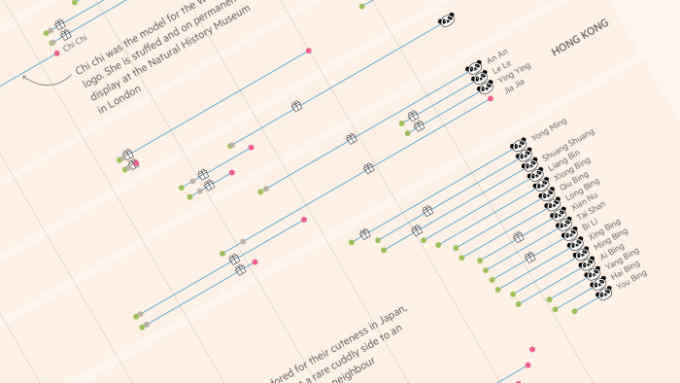

The FT revealed this week how Springer Nature, a German group that publishes leading periodicals including Nature and Scientific American, had blocked access to at least 1,000 academic articles in China that mention subjects deemed sensitive by Beijing, including Taiwan, Tibet and Hong Kong.

Cambridge University Press also acceded to a similar request from the Chinese authorities to block content. It reversed course after a backlash, pledging to “uphold the principle of academic freedom on which the university’s work is founded”.

Springer Nature, which claims to be the world’s biggest publisher of academic books, defended its actions, saying it was obliged to comply with “local distribution laws” and was trying to avoid its content being banned outright.

But China scholars accuse the company of abetting Chinese censors. James Millward, professor of Chinese history at Georgetown University, condemned Springer Nature for failing to disclose the scale of its censorship, beyond an admission that “less than 1 per cent” of its vast content library was affected.

The company is “effectively covering up and enabling the nature of the Chinese global censorship effort”, he said.

The scorn of academics will not, however, deter other publishers from following Springer Nature’s lead.

Sage Publications, another large commercial publisher of academic content, said it had not blocked any journals or articles in China but would not necessarily reject such requests.

“Should we be asked to withdraw any content in any country, we would engage in consultations with learned societies, editors and others shaped by the specific request in order to decide how to respond,” it said in a statement.

Other publishers were defiant.

University of Chicago Press, which publishes the highly regarded China Journal, said it had not yet blocked content in China but, if asked, would cut off access to institutions overseen by the government.

“If faced with a request by any government to remove material felt to be ideologically insupportable, our approach would be to stop making electronic access available to institutions overseen by that government,” said Michael Magoulias, director of journals at the University of Chicago Press.

It later clarified that this meant it would “remove all of our content from that market rather than accede to selective censorship”.

MIT Press, the publishing arm of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said political censorship was “antithetical to everything universities and university press publishing stand for”.

Lord Patten, chancellor of Oxford university, said recently that even though China was a “hugely important income stream” for the institution, Oxford University Press had not and would not block content.

But China experts fear that so long as publishers remain divided, Beijing will use its growing economic power and influence to pick them off one by one.

Jeffrey Wasserstrom, professor of Chinese history at the University of California, Irvine, called on publishers to resist Beijing and test its willingness to block access en masse to the world’s greatest producers of scientific and educational content.

“Some kind of co-ordinated effort is needed,” said Prof Wasserstrom, who is also editor of the Journal of Asian Studies, one of the Cambridge University Press publications the Chinese authorities tried to censor. “At a certain point, you have to walk away from the Chinese market, no matter how lucrative.”

This article has been amended to clarify that University of Chicago Press rejects censorship

Letter in response to this article:

Internal strife set China on a backward path / From Cecilia Li, New Territories, Hong Kong

Comments