Five things I’ve learnt about saving the world

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In the dying days of 2014, I wrote a story for the FT that people said was idiotic. It suggested that oil companies such as Shell and ExxonMobil would “cease to exist in their current forms within 35 years” under measures being discussed at UN talks on the global climate accord due to be struck in Paris the following year.

Fossil fuels would have to be phased out by 2050 under one option, or only used if countries could bring about something called net zero emissions. In other words, emissions would have to nosedive so much that any still being pumped out after 2050 could be offset by, say, planting forests that suck up carbon dioxide as they grow.

I had to put quotation marks around “net zero emissions” because the term was so new it had never appeared in the FT before. I was not sure it ever would again, considering how outlandish it seemed in 2014.

Then as now, the world got more than 80 per cent of its energy from oil, gas and coal, the fossil fuels that have powered countries’ economies for more than a century and employ millions of people worldwide. As one reader scoffed: “Odds that the climate talks will adopt the zero-fossil-fuels-by-2050 goal that this FT piece reports seriously = 0.”

He had a point. Twelve months later, when the Paris accord was finally hammered out, it did in fact include an awkwardly worded net zero target. But it was only for some time in the second half of this century, not 2050 precisely.

Today, less than four years later, net zero goals for 2050 (and even earlier) have mushroomed in a way I never imagined possible. More than 60 countries have either adopted such a target, or are discussing it, as public concern about climate change has rocketed up the rich world’s political agenda.

In April last year, Greta Thunberg was an unknown Swedish school student. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was an equally obscure 28-year-old New York activist. Extinction Rebellion consisted of about 15 people in a room in the Cotswolds. Now, all three are household names.

Perhaps this should not be a surprise. Just this week Venice has seen some of its worst flooding in decades; Australia has been struck by unusually fierce bushfires. Such events have magnified warnings of a worsening climate in people’s lifetimes, while rising emissions expose the inadequacy of 30 years of efforts to cut greenhouse gases.

Yet this year has still been surprising. Millions have marched in the streets demanding more emissions cuts. Green party candidates have made unexpected gains across Europe. Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal plan has inspired followers around the world.

“It’s as if you’re hammering and hammering on a ketchup bottle to get the sauce out and all of a sudden it comes out in one big splurge,” says Mark Lewis, head of sustainability research at France’s BNP Paribas Asset Management.

The shift reflects something that no one can easily ignore: a new set of rules on climate change that is altering the way we eat, dress, travel and work.

1. When change comes, it will be radical

When a fringe theory enters the political mainstream, it is put down to a shift in the Overton window — a concept named after US researcher, Joseph Overton, that describes how politicians tend to only champion policies deemed to be widely acceptable.

Net zero emissions goals have clearly become acceptable in a way they never were when I was the FT’s environment correspondent between 2011 and 2017, not least in the UK. It took British members of parliament less than 10 weeks to make the UK the first G20 country to put a 2050 net zero emissions target into law after Extinction Rebellion protesters paralysed London’s streets in April. But do voters, or indeed politicians, truly understand the scale of changes needed to make such goals a reality?

Probably not, says Professor Sir Ian Boyd, who was the UK’s chief environmental scientist for seven years until he stepped down in August.

“The net zero target is built on a wish and a prayer,” he told me. “We cannot stop greenhouse gas production without re-engineering our economy.” He thinks a net zero ministry may be needed to vet all department decisions, along with leadership and enlightened government policies which are, he says, “currently lacking”.

A taste of the challenge came in a recent UK parliamentary committee report that listed the gaps between the government’s climate aims and the policies needed to meet them.

Nearly 20,000 conventional cars should be removed from roads each week for the next 31 years on average. Last year only about 1,200 new ultra-low emissions vehicles were registered each week.

At least 15,000 homes a week should also switch from natural gas to lower carbon heating, not the 220 a week expected under current policies.

Enough trees should be planted to ensure net woodland growth of about 120 hectares a week, not the 20 hectares recorded last year.

Not all experts think the net zero challenge is impossible. “It is massive. It is unprecedented and people don’t realise how big it is,” says Professor Cameron Hepburn, director of Oxford university’s Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment. “But that actually doesn’t mean it’s grim,” he adds, pointing to the way new technologies, such as the mobile phone, can grow exponentially and displace older systems much faster than expected.

Governments will still need to act, however, and if history is a guide, they will struggle.

So far, governments around the world — and indeed banks and other businesses — have proved adept at boosting the supply of cleaner energy, with measures such as solar subsidies, green bonds or electric-car incentives. But few have tackled the more politically fraught task of cutting demand for fossil fuels. Some 46 countries have, for example, tried to stem fossil-fuel use by putting a price on carbon emissions. But the global average carbon price has only reached $2 per ton, nowhere near enough to make an impact.

China embodies the problem: the Middle Kingdom is a solar and wind power juggernaut — and also by far the world’s largest carbon emitter.

So what happens if all these net zero promises turn to dust? Will today’s climate marchers take a more radical turn? Even if they don’t, we could see a surge in climate consumerism.

2. Eco-consumers are on the march

At the age of 99, Australia’s Qantas Airways has survived the second world war, 9/11 and the 2008 financial crisis.

But this year, the airline’s chief executive, Alan Joyce, warned of an entirely different threat: widening green concerns that could end the era of mass air travel. Climate change was obviously a problem, he told an industry conference in Sydney in August. But European “flight-shaming” campaigns, and government plans to make flying more expensive were “retrograde steps” that could have serious consequences. We don’t want to “go back to the 1920s and not have air travel”.

He was right to be worried. Fossil-fuel subsidies have been in the public spotlight for years. A complex web of aviation subsidies has received less attention.

This is changing fast, at least in Europe. But airlines are not the only companies to be caught off guard by the rise of the climate consumer.

Not that long ago, offering shoppers a limited-edition £1 bikini might have sounded like a sensible marketing ploy for a British clothes store. But when online retailer Missguided tried the move in June, critics pounced. The group was accused of promoting a culture of exploitative, environmentally damaging fast fashion that had no place in a time of “climate emergency”.

Last month, the boss of Swedish fast fashion giant H&M warned that activists’ efforts to shame consumers could have “terrible” social consequences. Economic growth was still vital, Karl-Johan Persson told a Bloomberg reporter, echoing an argument made a few weeks earlier by Bernard Arnault, head of the luxury giant LVMH.

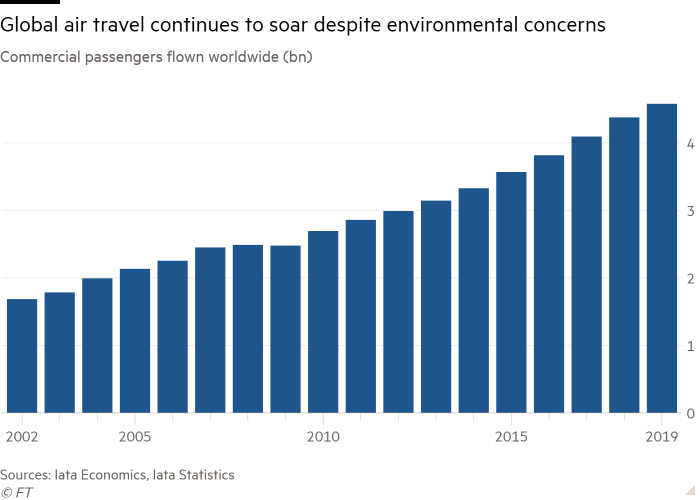

So far, there is no sign of a serious global climate revolt against fashion — or flying. Annual global passenger numbers rose 7 per cent last year to 4.4bn, bolstered by people in developing countries eager to follow the flight paths richer nations take for granted.

And any serious attempt to curb flights is bound to be contentious: a report commissioned by the UK government’s climate advisers recommending a ban on frequent-flyer schemes sparked excitable headlines. On top of that, not every climate-minded consumer can take a train instead of a flight.

But they do all eat food.

3. We’re all flexitarians now

In 2018, the Collins dictionary named “single-use” the word of the year as consumers across the world shunned plastic straws, bottles and bags. In 2019, the word was “climate strike”. Next year, it may well be “plant-based”.

Consider the US state of Georgia. The Peach State is the country’s top poultry producer — an unwelcome fact of life for Jill Howard Church, president of the Vegetarian Society of Georgia.

But in August, she watched as the internet filled with photos of long queues outside a KFC store in Atlanta selling a first: plant-based chicken nuggets from Beyond Meat, the US start-up whose market value at one point reached $12bn after its float in May.

“As someone who has tried to promote vegetarianism and veganism for literally decades, to all of a sudden see people lining up around the block for plant-based chicken nuggets is delightfully but surprisingly great,” she told me.

Beyond Meat’s share price has since subsided. But concerns about the climate cost of actual meat remain. The world’s growing appetite for beef in particular often requires carbon-storing trees to be cleared for cows that belch methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

Some analysts think meat substitutes will account for 10 per cent of the $1.4tn global meat industry over the next decade — which is good news for Lewis Hamilton. The Formula One racing driver announced he was investing in a group aiming to be the first plant-based burger chain this year, just weeks after London’s Goldsmiths university said it was going to be a beef-free campus as it declared a “climate emergency”.

No wonder meat producers, like airline bosses, are growing nervous.

Some US states with large cattle and poultry industries have begun to insist that foods labelled “burger” or “hot dog” must be made of animal flesh. Plant-based companies are fighting back, with consumers at their side in some places. The number of vegans in Britain quadrupled between 2014 and 2019 to 600,000, surveys show, and more than 40 per cent only switched last year, which suggests the trend is growing.

Green-minded US shoppers are forecast to spend up to $150bn on sustainable products by 2021, an increase of at least $14bn. That’s the good news. Other climate developments may prove more sobering.

4. Green trade wars are looming

Two days after the November 2016 US presidential election, I was in Marrakesh for a UN climate meeting, surrounded by people in shock. They had just discovered the US was to be led by a president who wanted to pull the country out of the Paris agreement. France’s ex-president, Nicolas Sarkozy, said if Donald Trump did this, Europe should impose a carbon tax on imported US goods.

In theory, taxing goods from climate laggards protects domestic industries from the brunt of green policies and prods the laggards to clean up their act. In reality, carbon border taxes have never been implemented at a national level. Some critics argue they are a protectionist ruse that would breach global trade rules. Others say they would be hard to implement and would invite costly retaliation, even though they would not cover enough high-carbon trade to be effective.

The European Commission has repeatedly quashed the idea, so I was not surprised when Commission officials in Marrakesh swiftly rejected Sarkozy’s suggestion.

But it is now very much in vogue. In July, Ursula von der Leyen promised to introduce a carbon border tax if elected European Commission president — which she was. US Democratic hopeful Joe Biden is promising a similar measure in a climate plan that singles China out by name and says the US should link its trade policy with its climate goals.

This year offered a glimpse of a future in which trade is used as a climate weapon: Brazil’s president Jair Bolsonaro sent the army in to fight devastating Amazon fires after EU leaders threatened to reject a South American trade deal.

It is tempting to imagine a US-EU carbon border tax club pressing China and other big emitters into faster action. But what would that mean at a time of rising trade tensions and nationalism?

It is 14 years since the UN published the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, a four-year study by more than 1,300 experts from 95 countries that looked at how humanity’s relationship with the environment might unfold over the 21st century.

Some of its bleaker scenarios sound increasingly familiar today. They describe a fragmented world of discredited global institutions and rising trade barriers in which problems such as climate change worsen and “global environmental surprises become common”.

For some industries, a painful future has already arrived.

5. Support for fossil fuels is faltering

In September, the New York Times dropped a small bombshell.

It ended its longstanding sponsorship of the 40-year-old Oil & Money conference, one of the biggest oil industry gatherings on the calendar.

“The subject matter of the conference gives us cause for concern,” a spokeswoman said, adding the paper had expanded its coverage of climate change and did not want “even the potential appearance of a conflict of interest”.

Climate activists have been pressing prominent institutions and investors to abandon fossil fuels for years. But victories, when they have come, have been largely at the expense of coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel.

In 2019, there are signs of a hardening mood. A month after the New York Times decision, London’s National Theatre announced an end to funding from Royal Dutch Shell and the Royal Shakespeare Company said it would cut its links with rival oil group, BP.

What if banks and other funding sources were pressured to follow suit?

It is hard to imagine. Last year, 33 banks provided $654bn to 1,800 fossil-fuel companies, according to the Rainforest Action Network campaign group, which says the total value of financing underwritten by these banks has risen every year since the 2015 Paris climate agreement was struck.

Outside the world of commercial banking, there have been hints of change. On Thursday, the multilateral lending giant, the European Investment Bank, made a striking decision to end any new financing for traditional fossil fuel projects from the end of 2021, including natural gas.

As a banker from another group told me recently: “It feels as if we’re reaching the stage where investors are treating oil and gas in the way they treated coal 10 years ago.”

If financial support for this industry ever faltered, it would spell a far more decisive climate shift than anything seen to date, and a potentially risky one if it led to a sudden flight of capital. That underlines the largest climate lesson of 2019: disruption is no longer avoidable.

I have no idea if today’s climate marches will endure, intensify or eventually fade away. It is equally unclear if any large country will ever take the steps needed to meet a net zero target. What is clear, however, is that the Overton window has shifted when it comes to expectations of climate action and whichever way governments respond, some form of disruption will ensue.

If nothing is done, there will be the physical disruption of climate change itself and perhaps more turbulent political and consumer activism. If serious action is taken to cut emissions, that too will spell sweeping changes. There are, in other words, no easy choices left, even if governments continue to behave as if there are.

In the first week of November, Boris Johnson’s government was supposed to have held a Green Great Britain Week to highlight the benefits and challenges of its groundbreaking net zero goal.

The event was postponed. Why? It clashed with the October 31 deadline for Britain’s exit from the EU. The Brexit timeline has been extended yet again. The deadline for dealing with the climate cannot be pushed away so easily. It has already arrived.

Pilita Clark is an FT columnist and a three-time winner of environment journalist of the year at the British Press Awards

Illustrations by Hilary Kirby with photos from AP, Backgrid, Reuters and Getty Images

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Listen and subscribe to Culture Call, a transatlantic conversation from the FT, at ft.com/culture-call or on Apple Podcasts

Comments