China’s soft power comes with a very hard edge

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

No animal in the world is more adored than the giant panda. There is a reason: the panda’s proportions — short fat limbs, oversized heads and big eyepatches — trigger the same neural reaction in us as the sight of human babies.

Anyone who has worked closely with these animals will, however, tell you they can be vicious. Almost every year there are reports of panda attacks in the small area of south-west China where they still exist in the wild.

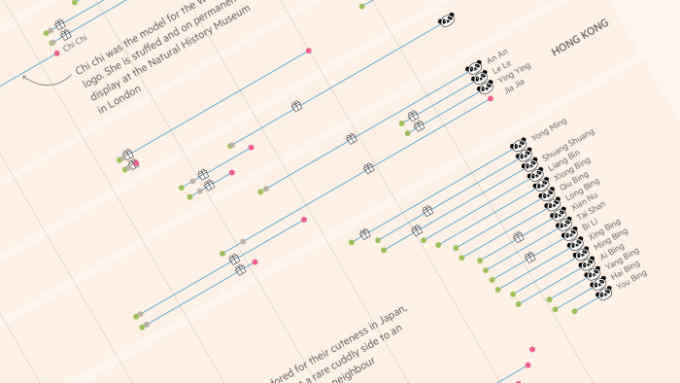

The panda has become a symbol of China, abetted by the ruling Communist Party’s practice of “panda diplomacy”. Since the 1950s, China has sent scores of the bears to dozens of countries. From North Korea and the Soviet Union, to Nixon’s America and Angela Merkel’s Germany, China has gifted or loaned the animals to governments it wants to befriend or reward.

The pandas come with hidden costs. China charges countries $1m a year for a pair of pandas and reserves the right to repatriate any offspring if it is displeased by the host country. President Xi Jinping signs off on every panda loan, but not until recipient countries have jumped through hoops and endured years of negotiations. China-based foreign diplomats complain about how skilful Beijing has become at manipulating governments and constituents in their home countries to increase demand for panda loans.

The Chinese government’s focus on breeding captive pandas to show in zoos and loan to foreign countries has come at the expense of efforts to protect the fragile forests in south-west China, where some 2,000 bears still survive in the wild. The recent success of panda breeding has even led some in China to question the value of protecting the species in the wild.

A tragedy looms if the Chinese government does not redouble its efforts to protect the panda’s habitat, home to numerous other rare species as well.

All of this, of course, has the marking of a rather obvious — but nonetheless very apt — metaphor. China’s efforts to build soft power outside its borders goes far beyond pandas — and in these areas, too, the People’s Republic needs to tread more lightly, and take a more reciprocal and less authoritarian approach.

China is entitled, as is any significant power, to bolster its soft power around the world. That Beijing should do so is particularly understandable. It is not part of the western club of nations. Its history, ideology, and economic system are all very different and so it needs to work hard to win acceptance from the group of countries that have held sway since the second world war. But what China should realise is that while western powers — and indeed the world — may well be prepared to accept its rising influence, they will not be amenable to outright interference.

There are many examples of intrusive uses of soft power by China. The forcing of publishers to censor their publications, the use of the United Front Work Department to infiltrate overseas Chinese groups in countries around the world, and the co-opting of Chinese student groups in Australia and elsewhere to protest against free speech are just a few. Companies are caught up, too. When South Korea’s government got on Beijing’s bad side for deploying a missile-defence shield, the South Korean chain Lotte saw its stores in China hit with fire-code violations. A government-backed boycott kept Chinese tourists out of South Korea, too.

Soft power is about the organic cultivation of mutual advantage and trust. In too many cases, China prefers to bully instead. There are not enough pandas left in China to obscure the difference between the two.

Comments